For Denver artist Jane Guthridge there’s something special about the sunshine in Colorado and the magic of big open skies. Armed with a camera, Guthridge hunts for these luminous moments, whether shimmering through a heat wave or bouncing across a frozen creek. These foraged fragments find new life in her amorphous sculptures, paintings and installations. Manipulating the radiant potential of paint, plastic and metal, she creates works that explore how light moves through nature. “My work all comes from patterns of light, its movement and rhythm,” she says.

Artist Jane Guthridge sometimes uses pastels to mimic natural light.

Artist Jane Guthridge sometimes uses pastels to mimic natural light.

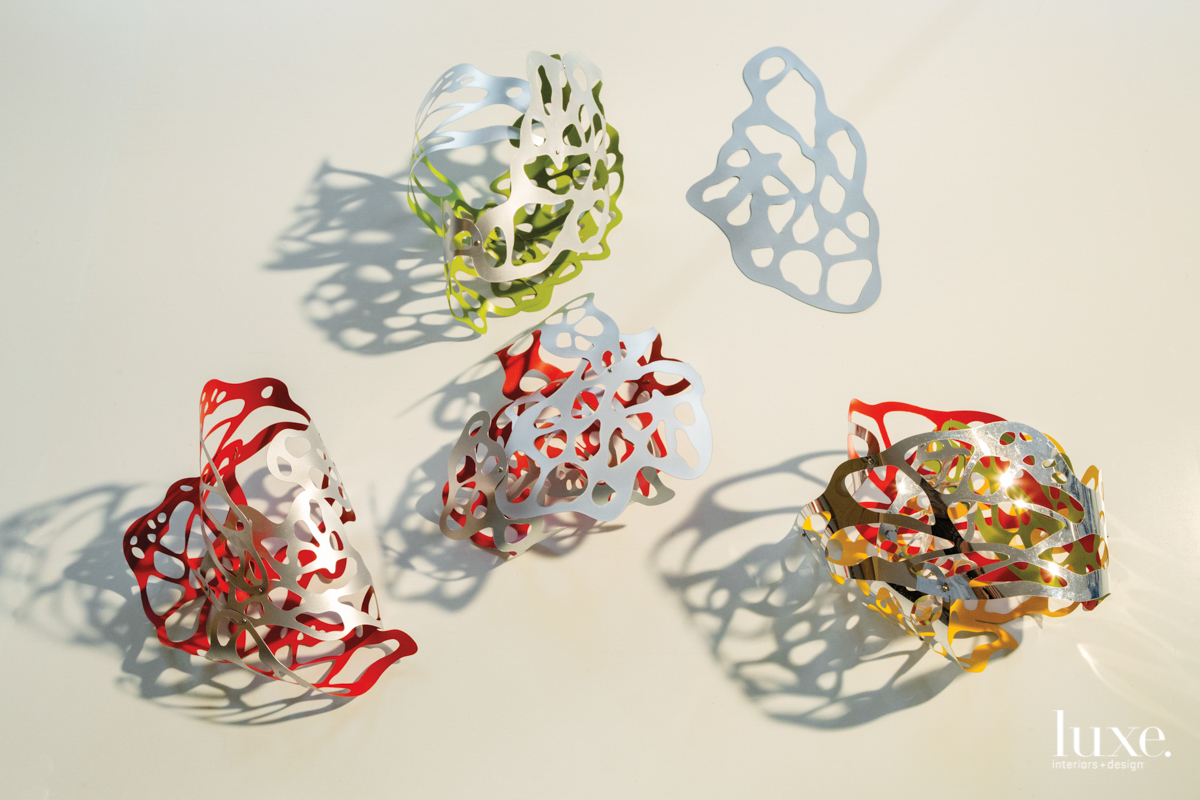

She molds film to make sculpture that casts compelling shadows. Much of her work has an ethereal quality.

She molds film to make sculpture that casts compelling shadows. Much of her work has an ethereal quality.

To compose her art, she uses computer models.

To compose her art, she uses computer models.

Perhaps Guthridge’s favorite natural phenomenon of all is komorebi—a Japanese term that describes the way sunshine filters through trees. These dappled patterns echo throughout her work, starting with her encaustic wax paintings on mulberry paper. “Where the paper becomes saturated with wax, it becomes translucent,” she says. “I love how it almost seems to suspend light.” This technique helped capture the way light diffuses through color, like sunshine through leaves. But the artist soon sought ways to also conjure komorebi’s shifting shadows. “I wanted to explore how shadows could become part of the piece,” notes Guthridge.

To create a more dimensional experience, the artist turned to sculpture using an unexpected source—Dura-Lar, a polyester film commonly used for stenciling. “It has this beautiful matte finish that holds light,” explains the artist.

Using her field photography as a reference, Guthridge plots abstract light patterns through a computer program and has these motifs laser-cut in massive sheets of film by fabricators. When filled with holes, the Dura-Lar “becomes fluid,” enabling her to create sculptural webs that can cascade down and across walls. She has a rough sketch of the composition that functions less like a map and more of “a calligraphic gesture.” This gives her freedom when arranging the Dura-Lar components together, shining a photo light though the structure “to see what the shadows are doing,” says Guthridge.

For her public art projects, the artist has turned to more durable Plexiglas and aluminum to recreate the same movements and shadows, so “they all react to light in the same way,” she explains. Guthridge also manipulates the luminous qualities of paint on her sculpture, whether applying soft acrylic washes to preserve translucency, or spraying on glossy finishes to add reflective shine.

Interacting with architecture marks the next stage of her sculptural experimentation, like her 2018 installation Suspended Light, where she strung together scraps of Dura-Lar from her previous wall sculptures to create teardrops of light curving around the staircase at The Elizabeth Hotel in Fort Collins. She recreated the same effect in resin-coated silk for her Shimmer installation, capturing sunshine from a skylight. The goal of these projects, and of all her work, “is to create an experience that feels bigger than ourselves,” says Guthridge. “I want to bring in the light wherever it can uplift us all.”