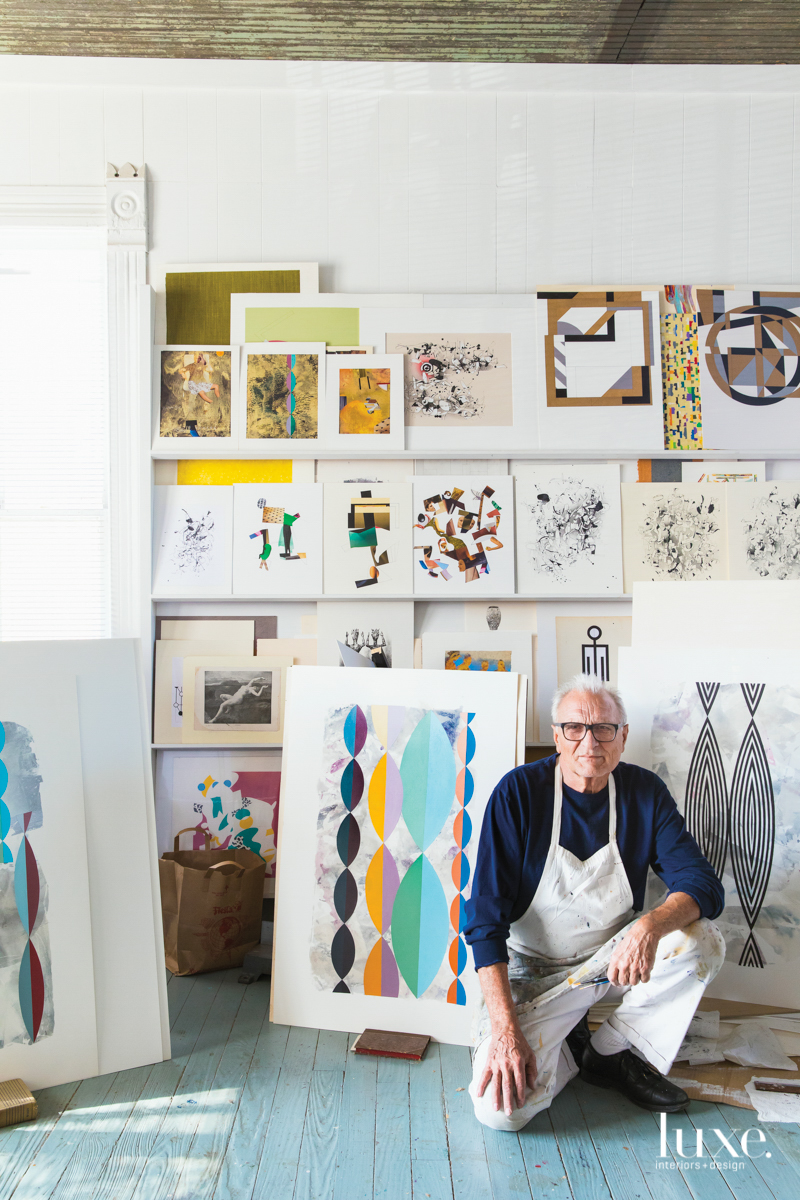

Austin-based artist and painter Helmut Barnett’s story isn’t the oft-told narrative of an artist born with paintbrush in hand. Although he enjoyed doodling in the margins of his school notebooks as a child, it wasn’t until he visited Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts at age 20–while serving as an Air Force radar technician stationed on Cape Cod–that he discovered his true calling. When his eyes locked on Dutch painter Jan Asselijn’s The Threatened Swan, it ignited a deep-seated desire in him to become an artist, no matter the odds. “My resolve coalesced into an unshakable drive,” says Barnett. “Nothing was going to stop me.”

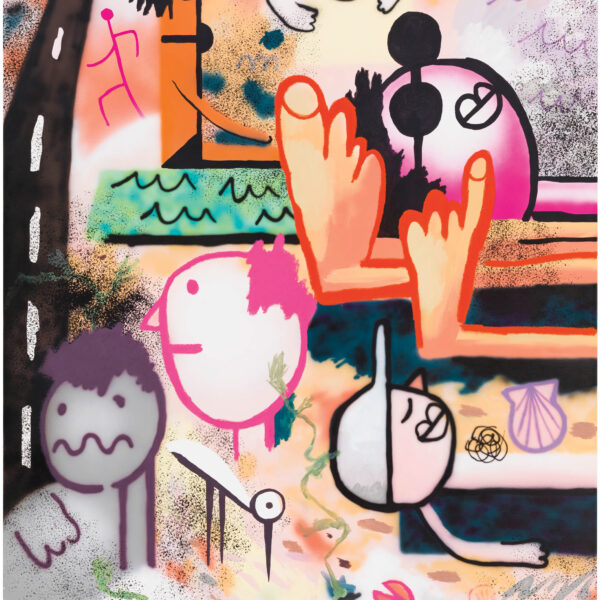

After that pivotal museum visit, Barnett began painting copiously, learning what he could from library books. Eventually, he studied art at the University of Texas, where he discovered his penchant for abstract. “I didn’t want to paint like people before me,” he says. “I wanted to be a modern painter, creating work that was distinctly my own.” More than 50 years later, Barnett now works out of a studio located in a century-old house. Light streams in through a large northern-facing window, illuminating a lifetime of work that is constantly evolving: abstract paintings, drawings and sculptures comprised of fluid lines and ethereal shapes.

His process is deeply intuitive: he first draws lines in rapid succession, pure instinct guiding his charcoal pencil. As shapes emerge, he colors them carefully in acrylic paint. It's not until the piece nears completion that he steps back and refines the composition, resulting in work as viscerally complex as it is expertly controlled.

His process is deeply intuitive: he first draws lines in rapid succession, pure instinct guiding his charcoal pencil. As shapes emerge, he colors them carefully in acrylic paint. It's not until the piece nears completion that he steps back and refines the composition, resulting in work as viscerally complex as it is expertly controlled.

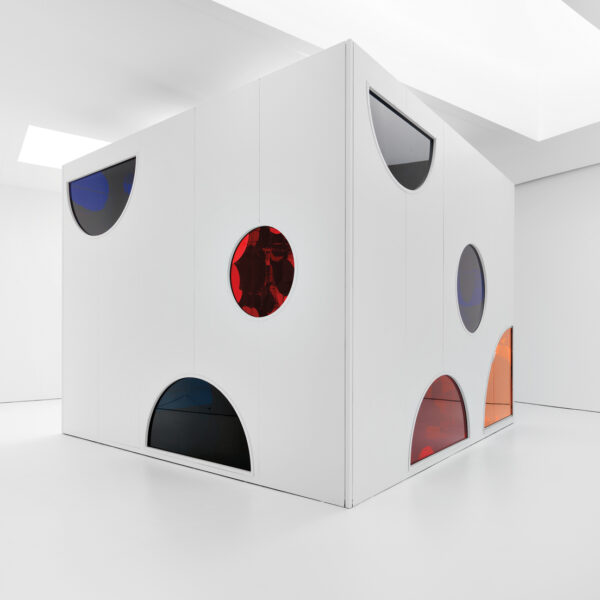

Barnett's sculptures are experiments based on shapes lifted from his two-dimensional work.

Barnett's sculptures are experiments based on shapes lifted from his two-dimensional work.

A wall in Barnett's studio contains quotes, postcards and other inspirational images.

A wall in Barnett's studio contains quotes, postcards and other inspirational images.

Strewn across Barnett's studio are works in various stages of completion.

Strewn across Barnett's studio are works in various stages of completion.

Barnett stores completed drawings in a flat file cabinet.

Barnett stores completed drawings in a flat file cabinet.

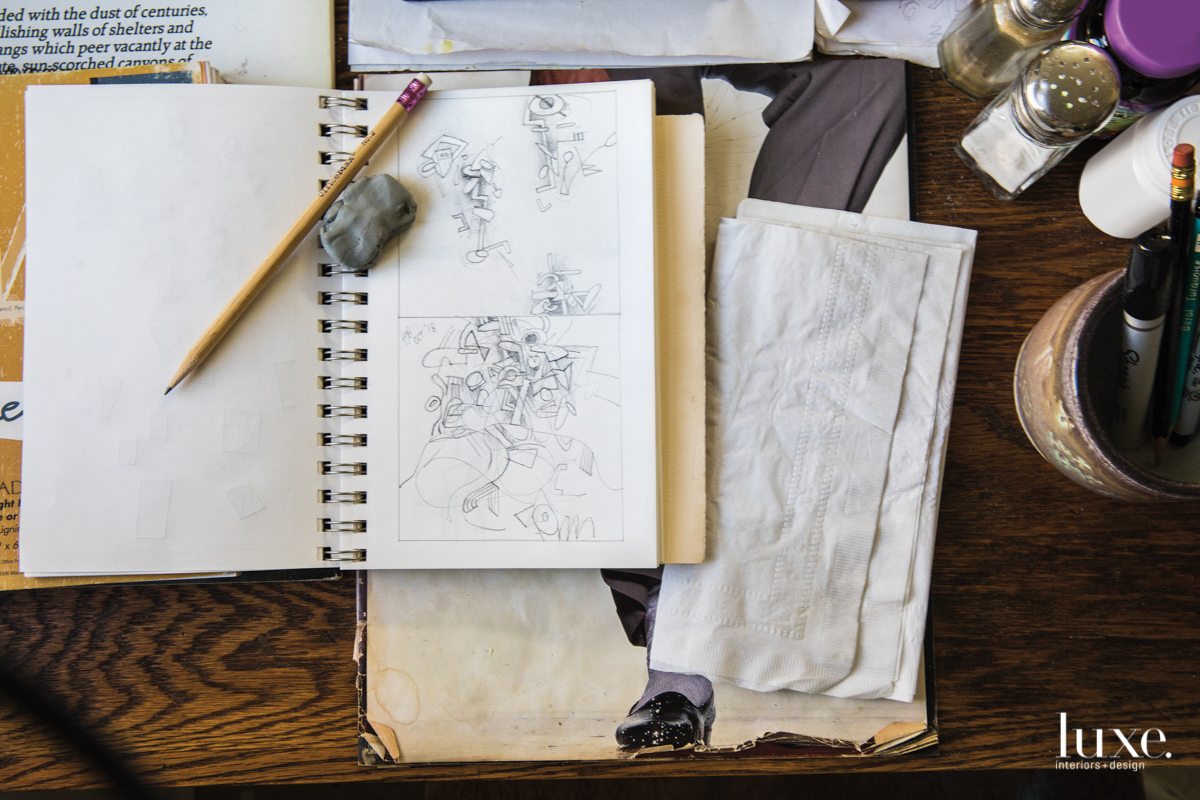

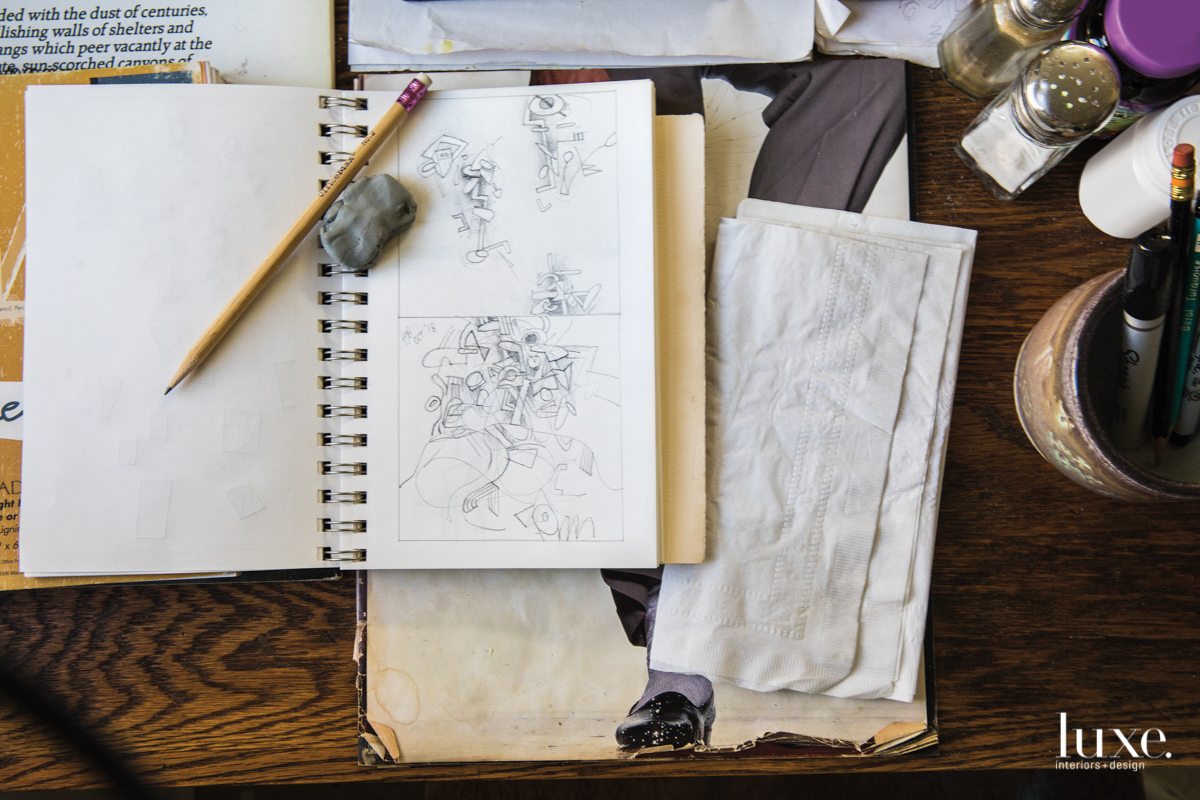

The artist often sketches while having lunch in his studio kitchen.

The artist often sketches while having lunch in his studio kitchen.

Strewn across Barnett’s studio floor are paintings in various stages of completion–he often hops from one to the next, allowing them to breathe and his mind to stew. His process is deeply intuitive: he first draws lines in rapid succession, his charcoal pencil guided by pure instinct. As shapes emerge, he colors them carefully in acrylic paint. It’s not until the piece is almost finished that he steps back and refines the composition, resulting in work as viscerally complex as it is expertly controlled. “It’s very important to me to create art that is well done and intelligent,” he says. “Little changes–a line here, a shape there–make all the difference.”

Barnett’s time in the Air Force continues to inspire him today. He spent his downtime between 16-hour flight missions voraciously reading art and ancient history books, and Greek pottery imagery and figurative form often weave organically through his work. He also credits his 1,600-square-foot studio as a source of inspiration. “This is my sanctuary,” he says. “When I’m here, I’m in my element and undisturbed–it’s a breeding ground for ideas.” In fact, it’s difficult to pull him away, as Barnett often works a 50-hour week, including weekends–although he does enjoy swimming laps midday for exercise and often heads home early during the winter to build a fire for his wife, Shelby.

Against his studio’s walls now tower several large empty canvases. Their size is imposing, but Barnett isn’t concerned. After decades of honing his craft, he’s reached a place of unwavering confidence. “I don’t worry about where the work will be tomorrow but instead let it carry itself,” says Barnett, who is represented by Wally Workman Gallery. The artist, who honed his talent through passion and hard work, adds, “The essence of what I do is a love of the act of drawing and painting–lines, form and color, in all their infinite possibilities.”